Camera obscura

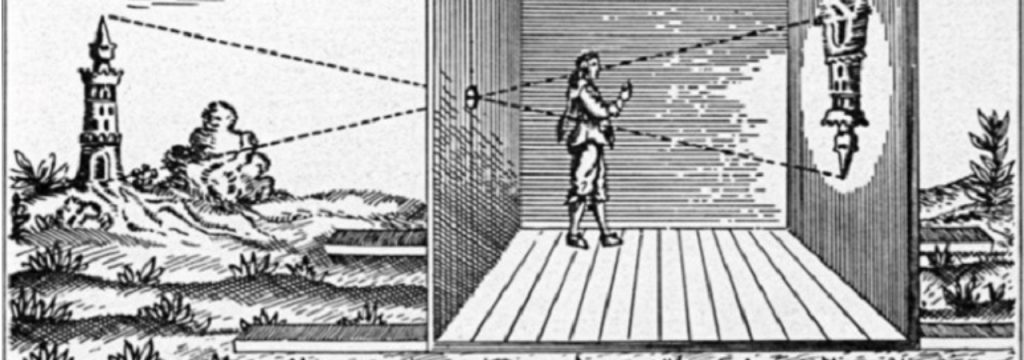

| In the eleventh century, people noticed that if there was a small hole in one wall of a darkened room then the light coming through the hole would make a faint picture on the opposite wall of the scene outside the room. A room like this was called a camera obscura. Artists later used a box “camera obscura” with a lens in the hole to make the picture clearer. But it was not possible to preserve the image that was produced in the box.

In 1727, Johann Heinrich Schulze mixed chalk, silver, and nitric acid in a bottle. He found that when the mixture was exposed to the light it became darker. In 1826, Joseph Nicéphone Niepce put some paper dipped in a light-sensitive chemical into his camera obscura which he left on a window. The result was probably the first permanent photographic image. The image Niepce made was a “negative”, a picture where all the white parts are black and all the black parts are white. Later, Louis Daguerre found a way to reverse the black and white parts to make “positive” prints. But when he looked at the pictures in the light, the chemicals continued to react and pictures went dark. In 1837, he found a way to “fix” the image. These images are known as daguerreotypes. Many developments were made in the nineteenth century. Glass plates coated with light-sensitive chemicals were used to produce cheap, sharp, positive prints on paper. In the 1870s, George Eastman proposed using rolls of paper film, coated with chemicals, to replace glass plates. Then, in 1888, Eastman began manufacturing the Kodak camera, the first “modern” lightweight camera which people could carry and use. |